Like other promising social trends before, the Sharing City seems to have slid down in the hype cycle, where it is now stuck in the trough of disillusion. A few years ago, the prospects of car sharing, of renting a place in any city of the world, of renting a car between individuals, and all of that at a very reasonable price, were appealing to everybody. Last September, Julian Agyeman, a professor at Tufts university, summed up this hope in the Time (http://time.com/3446050/smart-cities-should-mean-sharing-cities/):

‘Sharing the whole city’ should become the guiding purpose of the future city. (…) It redefines what ‘smart cities’ of the future might really mean—harnessing smart technology to an agenda of sharing and solidarity, rather than the dumb approaches of competition, enclosure and division.

Alas, since, most of us have taken a ride in a overfilled minivan or have spent a night in an Airbnb apartment looking exactly like a soulless hotel room, the filth in bonus.

We can all agree that many aspects of a sharing city became parts of a juicy business, and that is also what the Time article deplores. Fortunately, many people become interested in those abuses. And they look at the data. The data are just there, on the Internet. Airbnb, BlablaCar, Drivy, all these websites are just waiting to be scraped. What do we expect from digging in this data? Are we one step from burying the utopian sharing city or are we saving it by using urban data for better regulation?

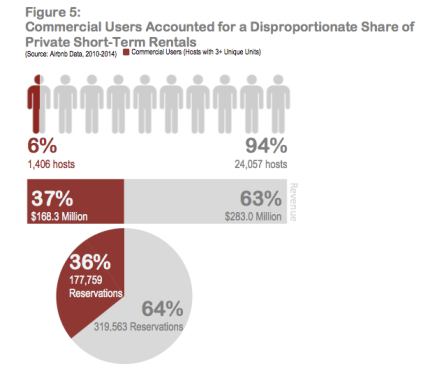

Last October, the attorney general of New York released a very interesting report called “Airbnb in the city” (http://www.ag.ny.gov/pdfs/Airbnb%20report.pdf), in which he unveils many laws violations. Analyzing all the city data from 2010 to 2014, he made major findings. For instance, 6% of the hosts represent 37% of all host revenue, mainly because these hosts are offering numerous unique units, up to hundreds. The report calls these hosts “Commercial users”. Almost half (2000 out of 4600 for the year 2013) of the rental units are illegally used as long-term sublets. For these units, the nights booked accounting for more than half of the total nights in a year. The figures below display some shocking findings of the report.

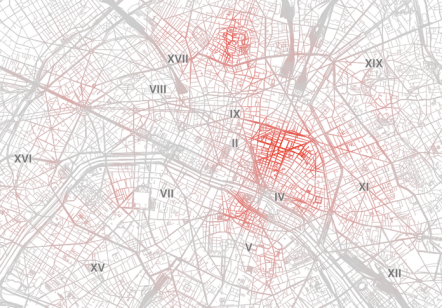

After the release of the report, some journals related the stories of these “Commercial users”. The New York Times, for example, interviewed an “entrepreneur” who, “at his peak, he said, (he) managed 12 listings and hired a team of cleaners, greeters and handymen to keep his scatter-site hotel operating” (http://www.nytimes.com/2014/11/30/magazine/the-business-tycoons-of-airbnb.html). The Airbnb data revolution stirred interest elsewhere and just after, in November, was published an article about Airbnb in the swiss newspaper Le Temps. A data journalist, focusing on the Geneve market, scraped the data directly from the Airbnb website and commented the findings (http://www.letemps.ch/Page/Uuid/50b60f32-6800-11e4-8073-f0fefc2ac70d/Avec_Airbnb_ma_petite_entreprise_de_location_ne_conna%C3%AEt_pas_la_crise). The method was quite different from forcing Airbnb to cooperate and share the data, as the NY attorney general was able to do, but proved itself quite effective as well. The journalist nicely described how to easily scrap the data, even when you are not an expert at that kind of things. She even shared the code she used. Then she explained how she identified multi-renting hosts who were making a business out of the website. Of course, this amateur technique does not work against real specialists who juggle between different accounts, but it shows how you can easily identify obvious misemploys of the system. When you cannot eradicate abuses, you can at least make life more difficult for those committing them. With this article, a trend was born. In a Parisian blog, a freelance journalist applied the method explained in Le Temps and came up with a nice visualization of the Paris market (http://dansmonlabo.com/2014/11/24/airbnb-la-carte-des-prix-de-location-a-paris-et-ce-quon-y-apprend-415/).

It showed that the multi-renting hosts amounted to almost 20% of the total hosts. The journalist also focused on the repartition of the places rented and the prices of the housing units compared to the housing market. Today, I am willing to bet that there will be other articles in other cities shedding light on new particular Airbnb markets.

We have at least learned, or confirmed, three things from all these recent articles. First, you cannot expect the startups and companies that are the symbols of the sharing city to fix things by themselves. These companies do not pursue the same ideals and motives than the people who actually get excited about the new sharing system. They look after their own profit, and that is what most importantly matters to these companies. The Airbnb staff are supposed to be the best experts of data mining and yet, they never seemed to mind the clearly illegal uses that the prosecutor of New York unburied. Second, making public the abuses does work, and even more if it is done by a public authority. A “commercial user” confessed that he decreased his renting activity after the release of the NY report, and we can guess there are many people in his situation. Likewise, the multi-owners directly contacted by Le Temps will think twice before making business again on Airbnb. All this should set an example. Cities should have a right to access any data that could reveal patent illegal behaviors, in part because those latter lead to more inequality. Third, there is an opportunity for everyone to identify and denounce abuses. For those who fight for an equal, sustainable and livable city, the tools are just out there, ready to be used. They are called API, scraping, data analysis, spatial visualization, etc. It is a task worth doing, because in the Airbnb case, what is at stake is the good health of a housing market already distressed. What we need last are apartments going out of the long-renting market to go on Airbnb.

In conclusion, I strongly believe that the Airbnb case opened a door to better regulations of innovative services in cities. I personally buttress the motives and principles of the sharing city and I don’t want them to be ruined by greed. Using simple analysis on the internet, everybody can contribute to tracing those abuses. However, I don’t stand up for a regulation coming mainly from an already busy internet community. On the contrary, I want urban leaders to take their responsibility and to make everything possible to force companies to share their data. City governments should be able to prevent patent misuses of modern services. If they can’t, we are sadly heading towards increasingly dividing cities.

Very interesting article ! It sheds light on a very important topic, especially when you think of the fact that this type of practices excludes the houses and apartments from the market of permanent inhabitant and makes everyone pay a higher price for renting… Do you know if the “commercial users” or other people committing infractions were punished (exclusion from the airbnb site, fine, …) ?

LikeLike

As far as I know, there have been three fines for illegal short-rentals this year and last year.

In Barcelona, the firm AirBnB itself was fined 30 000 euros. It is worth mentioning that the city of Barcelona is also very strict towards Uber, with fines up to 6 000 euros for drivers using the app. In Paris, a tenant was fined 2 000 euros for short letting his apartment without the assent of the real estate company he is renting from. The company sued him for illegal renting. Finally, in New York, a man was fined 2 400 dollars for short letting his place while he was not himself sleeping in his apartment. The fine was overruled because it was shown that the flat mate was present and it was therefore legal to short let a room.

People tend to forget there are many rules you have to respect for renting your place on AirBnB. For instance, you cannot ask a price higher than what you pay yourself for the apartment. You cannot rent your place if you are not present in the place yourself. Needless to say that very few people, if not nobody, respect that.

I advise you to read a very interesting article on this topic: http://www.nytimes.com/2014/09/22/technology/sharing-economy-faces-patchwork-of-guidelines-in-european-countries.html . It shows the diversity of guidelines in European countries concerning services like AirBnB and Uber.

LikeLike